Nichiren was born on the seacoast of the south eastern corner of japan, in a fishing village surrounded, on the north by undulating hills and washed by the dark blue waves of the Pacific Ocean on the south. Tidal waves have washed away the part of the seacoast where his father’s house stood, and today the spot is pointed out in the depths of the wonderfully clear water, on the rocky bottom of the sea, where lotus flowers are said to have bloomed miraculously at the birth of the wonderful boy. His father was a fisherman, and doubtless the boy was often taken out in the father’s boat, and must have enjoyed the clear sky and pure air of the open sea.

When in later years, during his retirement in the mountains, a follower sent him a bunch of seaweed to eat, the old hermit wept as he called to mind his early memories of the seaweeds, which are, indeed, a charming sight as they are seen through the transparent water. Far away from the effeminating air of the Imperial capital, far away from the turmoils and agitations of the Dictator’s residence, the boy grew up in the fresh and invigorating atmosphere of a seaside village, in the midst of unadorned nature wooded hills and green trees, blue waters and sandy beaches. The inspiration of nature and the effect of association with the simple, sturdy people are manifest in each step of Nichiren’s later career, in his thoughts and his deeds.

The new light was to come out of the East for the salvation of the Latter Days this prophetic zeal of Nichiren is in large measure to be attributed to his idea about his birth, and to the surroundings of his early life.

In 1233, when the boy was eleven years old, his parents sent him to a monastery on the hill known as Kiyozumi, the “ Clear Luminosity,” near his home. The reason is not given, but it was in no way an exceptional or extraordinary step, in those days many a father did the same, whether from motives of piety or for the sake of the boy’s future career. The peaceful and innocent days of the boy novice passed, he was made an ordained monk when he was fifteen years old, and the religious name given by his master was Rencho, or “ Lotus-Eternal. ” Doubts grew with learning, because too many tenets and practices were included in the Buddhist religion of his days, and the keen-sighted youth was never satisfied with the incongruous mixture in the religion he was taught.

“My wish had always been”, he tells us in his later writings, to sow the seeds for the attainment of Buddhahood, and to escape the fetters of births and deaths. For this purpose I once practised, according to the custom of most fellow-Buddhists, the method of repeating the name of Amita Buddha, putting faith in his redeeming power.

But, since doubt had begun to arise in my mind as to the truth of that belief, I committed myself to a vow that I would study all the branches of Buddhism known in Japan and learn fully what their diverse teachings were.” His distress of mind was, however, not over a merely intellectual problem, but was a deeply religious crisis; and, indeed, the young monk was then passing through so violent a struggle of religious conversion that he at last fell into a swoon, following a fit of spitting blood. It is said that during this swoon he saw, in vision, Kokuzo, the deity of wisdom.

This happened when Rencho was seventeen years old, and in the next year we find him studying under a teacher of Amita-Buddhism in Kamakura, the residence of the Commissioners. The uneasiness of the young monk was not allayed, and his quest of truth was not satisfied by the teachers who were accessible in the provinces. Rencho then went to Hiei, the greatest centre of Buddhist learning and discipline, where he stayed from 1243 to 1253, pursuing a varied course of study and training. During these year he also visited other centres of Buddhism, where special branches of Buddhism were taught and practised, and extended his study even to Shinto and Confucianism.

The results of all this study and investigation are shown, not only in the erudition of his later writings, but in the comprehensive breadth of his doctrine. But the range of his studies never diverted him from his central problem: What is the true form and the unique truth of Buddhism ? On the contrary, as he progressed in knowledge, the conviction gradually grew strong in his mind that the truth is one, and that the essence of the Buddhist religion nay, of human life is not manifold. “I had gone to many centres of the religion, he says in reminiscence, during those twenty years, in the quest of Buddhist truths. The final conclusion I arrived at was that the truth of Buddhism must be one in essence.

Many people lose themselves in the labyrinth of learning and studies, through thinking that every one of the diverse branches might help to the attainment of Buddhist ideals. Wherein, then, did the young zealot find the unique truth ?

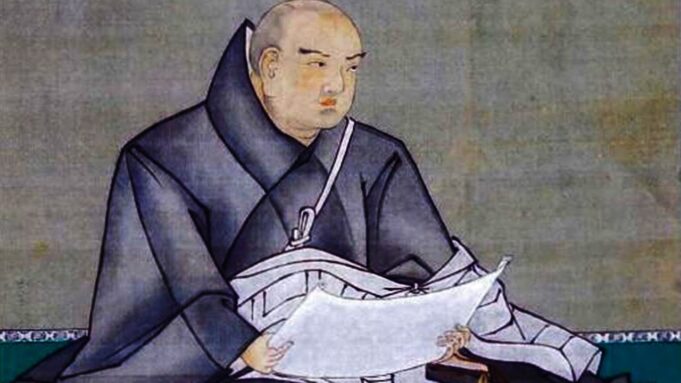

Fierce internal struggles, wide study, and prolonged thought brought this sincere seeker after truth to the final conviction that the scripture, The Lotus of Truth, was the deposit of the unique truth, the book in which Buddha had revealed his real entity, and on which the great master Dengyo had based his religion and institutions. The name Rencho was now exchanged for Nichiren, which means Sun-Lotus; the Sun, the source of universal illumination, and the Lotus, the symbol of purity and perfection, were his ideals. Nichiren’s firm belief was that the Lotus of Truth was not only the perfect culmination of Buddhist truth, but the sole key to the salvation of all beings in the latter days of degeneration.

Thus, all other branches of Buddhism, which deviated from the principle of the exclusive adoration of this scripture, were denounced as untrue to Buddha, as we have already seen in Nichiren’s condemnation of the prevalent forms of Buddhism. Nichiren’s idea was the restoration of Buddhism to its original purity, and to the principles propounded by Dengyo; but what he understood by restoration was quite different from our modern idea of historical criticism. The truths are eternal, but the method should be a simple one, available for all, especially for men of the Latter Days, and without regard to differences among them in wisdom and virtue.

These convictions of Nichiren had a complicated background of philosophical thought, in accord with the general trend of Buddhist speculation, and as a result of his learning. But all these doctrines and arguments were fused by the white-heat of his faith and zeal; that is, he simplified the whole practice of religion to an easy method, that of uttering the “ Sacred Title “ of the Scripture.

The Sacred Title meant the exclusive adoration of the truths revealed in the book, Lotus Sutra, practised in the repetition of the formula: “Nam Myoho-renge-kyo, that is, “Adoration be to the Scripture of the Lotus of the Perfect Truth! ” This formula is, according to Nichiren, neither merely the title of the book, nor a mere symbol, but an adequate embodiment of the whole truth revealed in that unique book, when the formula is uttered with a full belief in the truths therein revealed, and with a sincere faith in Buddha as the lord of the world. Nichiren’s thought on this point will be more fully expounded further on, but here let us see just what he meant by the Lotus of Truth.

He wrote later, in 1275, explaining his position, as follows:

“All the letters of this Scripture are indeed the living embodiments of the august Buddhas, who manifested themselves in the state of supreme enlightenment. It is our physical eyes that see in the book merely letters. To talk in analogy, the pretas (hungry ghosts) see fire even in the water of the Ganga, while mankind sees water, and the celestial beings see ambrosia. This is simply due to the difference of their respective karmas, though the water is one and the same, The blind do not perceive anything in the letters of the Scripture; the physical eyes of man see the letters, those who are content with self annihilation see therein emptiness, whereas the saint (Bodhisattva) realizes therein inexhaustible truths, and the enlightened (Buddhas) perceive in each of the letters a golden body of the Shakyamuni Buddha. This is told in the holy text in the teaching that those who recite the Scripture are in possession of the Buddha’s body. Nevertheless, prejudiced men thus degrade the holy and sublime truth”

What, then, is taught in this book which Nichiren esteemed so highly, and what led Nichiren to his conviction ? The Lotus of the Perfect Truth, or Myoho-renge-kyo in Sinico-Japanese, is an equivalent of the extant Sanskrit text, Saddharma-pundarika-sutra. The book circulated in China and Japan in a Chinese translation produced by Kumarajiva in 407 BC. The translation was so excellent in the beauty and dignity of its style that it supplanted all other translations, and was regarded as a classical writing in Chinese, even apart from its religious import.

It was on the basis of this book that Chi-ki, the Chinese philosopher- monk of the sixth century, created a system of Buddhist philosophy of religion. This system was called the Tendai school, from the name of the hill where Chi-ki lived; and it was this system of religious philosophy and philosophical religion that was transplanted by Dengyo to Japan as the corner-stone of his grand ecclesiastical institutions.

Nichiren discovered, during his stay on Hiei, that Dengyo’s far-reaching scheme of unifying Japanese Buddhism in his institutions on Hiei had been totally obscured and corrupted by the men of Hiei itself, who had imported de- generate elements of other systems. This thought induced Nichiren to make a zealous attempt at restoring Dengyo’s genuine Buddhism, and therefore the orthodox Tendai system. This could be done only by concentrating thought and devotion upon the sole key of Buddhist truths, as promulgated by the two great masters that is, upon the Lotus sutra, especially in Kumaraziva’s version.

The book, Lotus sutra , was acknowledged by nearly all Buddhists to be sermons delivered by Buddha in the last stage of his ministry, and, as such, called forth the highest tributes from most Buddhists of all ages. Critical study of Buddhist literature will doubtless throw more light on the formation and date of the compilation; but even apart from minute analysis, we can safely characterize the book as occupying the place taken in Christian literature by the Johannine writings, including the Gospel, the Apocalypse, and the Epistles. The chief aim of the Lotus sutra, both according to the old commentators and to modem criticism, consists in revealing the true and eternal entity of Buddhahood in the person of the Shakyamuni buddha, who appeared among mankind for their salvation.

In other words, the main object is to exalt the historic manifestation of Buddha and identify his person with the cosmic Truth {Dharma), the universal foundation of all existences.